- Glyph Designer 2 1 – Bitmap Font Generator Minecraft 1.7.10

- Glyph Designer 2 1 – Bitmap Font Generator Minecraft Download

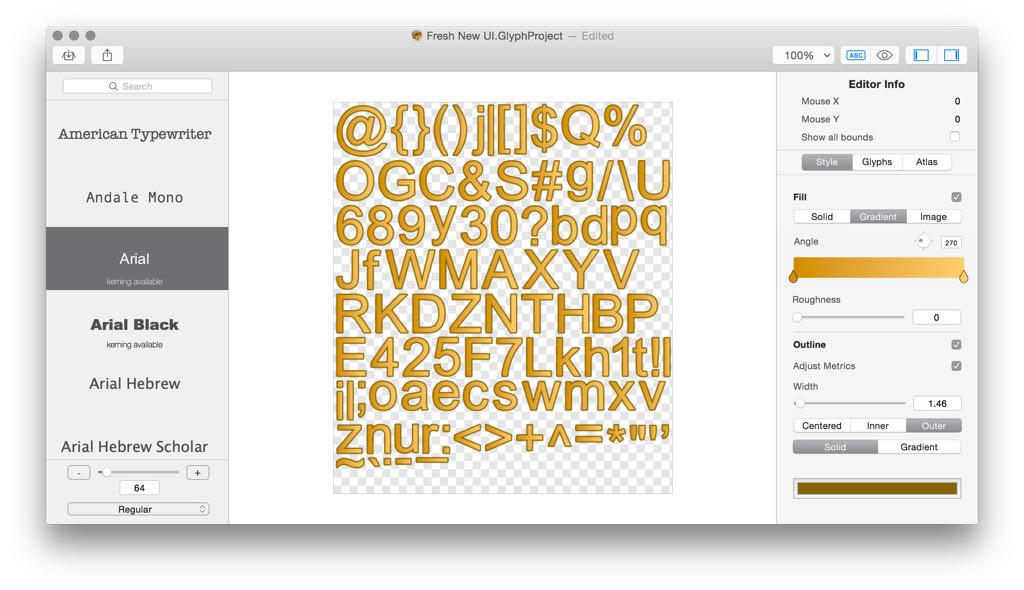

Bitmap Font Importer. Bitmap Font Importer is just perfect Unity asset plugin to import any custom bitmap font to your project. It easy imports any bitmap font generated by third party tools like:littera, bmGlyph, Glyph Designer 2, ShoeBox or Bitmap Font Generator. Thiks @Xylph, this origin code form here. Free; Auto Import bitmap fonts. Glyph Designer is a powerful bitmap font designer. Create beautiful designs using highly configurable effects, definable backgrounds, custom images, editable glyph metrics and more. Make the most of your screen with smart zooming and full screen support. Target hundreds of devices on multiple platforms with support for over 15 frameworks out. GlyphTypeFace: Specifies a physical font face that corresponds to a font file on the disk., useful to parse a.TTF file and build glyphs from it. GlyphRun: Represents a sequence of glyphs from a single face of a single font at a single size, and with a single rendering style, with many usefull properties and methods (for example, you can build. Open Bitmap Font Generator (BMF) and you will see something like bellow. Go to Options-Font Settings or hit 'F' on your keyboard and a small dialog will pop up. There you can select your desired font and its size etc. Now you will need to find out how the original bitmap was generated. Creation and Use of Bitmap Font Software. We use freeware Bitmap Font Generator for generating bitmap fonts, and explain how to use bitmap fonts in QICI Engine. The following are some other tools that also generate output in the same format and are widely used in the industry today: Littera - free web application; Glyph Designer paid app for Mac.

II. Managing Glyphs

1. Glyph Metrics

Glyph metrics are, as the name suggests, certain distances associated with each glyph that describe how to position this glyph while creating a text layout.

There are usually two sets of metrics for a single glyph: Those used to represent glyphs in horizontal text layouts (Latin, Cyrillic, Arabic, Hebrew, etc.), and those used to represent glyphs in vertical text layouts (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, etc.).

Note that only a few font formats provide vertical metrics. You can test whether a given face object contains them by using the macro FT_HAS_VERTICAL, which returns true if appropriate.

Individual glyph metrics can be accessed by first loading the glyph in a face's glyph slot, then accessing them through the face->glyph->metrics structure, whose type is FT_Glyph_Metrics. We will discuss this in more detail below; for now, we only note that it contains the following fields.

- width

- This is the width of the glyph image's bounding box. It is independent of the layout direction.

- height

- This is the height of the glyph image's bounding box. It is independent of the layout direction. Be careful not to confuse it with the ‘height' field in the

FT_Size_Metricsstructure. - horiBearingX

- For horizontal text layouts, this is the horizontal distance from the current cursor position to the leftmost border of the glyph image's bounding box.

- horiBearingY

- For horizontal text layouts, this is the vertical distance from the current cursor position (on the baseline) to the topmost border of the glyph image's bounding box.

- horiAdvance

- For horizontal text layouts, this is the horizontal distance to increment the pen position when the glyph is drawn as part of a string of text.

- vertBearingX

- For vertical text layouts, this is the horizontal distance from the current cursor position to the leftmost border of the glyph image's bounding box.

- vertBearingY

- For vertical text layouts, this is the vertical distance from the current cursor position (on the baseline) to the topmost border of the glyph image's bounding box.

- vertAdvance

- For vertical text layouts, this is the vertical distance used to increment the pen position when the glyph is drawn as part of a string of text.

As not all fonts do contain vertical metrics, the values of vertBearingX, vertBearingY and vertAdvance should not be considered reliable if FT_HAS_VERTICAL returns false.

The following graphics illustrate the metrics more clearly. In case a distance is directed, it is marked with a single arrow, indicating a positive value. The first image displays horizontal metrics, where the baseline is the horizontal axis.

For vertical text layouts, the baseline is vertical, identical to the vertical axis. Contrary to all other arrows, bearingX shows a negative value in this image.

The metrics found in face->glyph->metrics are normally expressed in 26.6 pixel format (i.e., 1/64th of pixels), unless you use the FT_LOAD_NO_SCALE flag when calling FT_Load_Glyph or FT_Load_Char. In this case, the metrics are expressed in original font units.

The glyph slot object has also a few other interesting fields that eases a developer's work. You can access them through face->glyph->xxx, where xxx is one of the following fields.

- advance

- This field is a

FT_Vectorthat holds the transformed advance for the glyph. That is useful when you are using a transformation throughFT_Set_Transform, as shown in the rotated text example of part I. Other than that, its value is by default (metrics.horiAdvance,0), unless you specifyFT_LOAD_VERTICALwhen loading the glyph image; it is then (0,metrics.vertAdvance). - linearHoriAdvance

- This field contains the linearly scaled value of the glyph's horizontal advance width. Indeed, the value of

metrics.horiAdvancethat is returned in the glyph slot is normally rounded to integer pixel coordinates (i.e., being a multiple of 64) by the font driver that actually loads the glyph image.linearHoriAdvanceis a 16.16 fixed-point number that gives the value of the original glyph advance width in 1/65536th of pixels. It can be use to perform pseudo device-independent text layouts. - linearVertAdvance

- This is the similar to

linearHoriAdvancebut for the glyph's vertical advance height. Its value is only reliable if the font face contains vertical metrics.

2. Managing Glyph Images

The glyph image that is loaded in a glyph slot can be converted into a bitmap, either by using FT_LOAD_RENDER when loading it, or by calling FT_Render_Glyph. Each time you load a new glyph image, the previous one is erased from the glyph slot.

There are situations, however, where you may need to extract this image from the glyph slot in order to cache it within your application, and even perform additional transformations and measures on it before converting it to a bitmap.

The FreeType 2 API has a specific extension that is capable of dealing with glyph images in a flexible and generic way. To use it, you first need to include the FT_GLYPH_H header file.

a.Extracting the Glyph Image

You can extract a single glyph image very easily. Here some code that shows how to do it.

The following steps are performed.

- Create a variable named

glyph, of typeFT_Glyph. This is a handle (pointer) to an individual glyph image. - Load the glyph image in the normal way into the face's glyph slot. We don't use

FT_LOAD_RENDERbecause we want to grab a scalable glyph image that we can transform later on. - Copy the glyph image from the slot into a new

FT_Glyphobject by callingFT_Get_Glyph. This function returns an error code and setsglyph.

It is important to note that the extracted glyph is in the same format as the original one that is still in the slot. For example, if we are loading a glyph from a TrueType font file, the glyph image is really a scalable vector outline. You can access the field glyph->format if you want to know exactly how the glyph is modeled and stored.

A new glyph object can be destroyed with a call to FT_Done_Glyph.

The glyph object contains exactly one glyph image and a 2D vector representing the glyph's advance in 16.16 fixed-point coordinates. The latter can be accessed directly as glyph->advance

Note that unlike other FreeType objects, the library doesn't keep a list of all allocated glyph objects. Jixipix premium pack 1 1 12 oz. This means you have to destroy them yourself instead of relying on FT_Done_FreeType doing all the clean-up.

b. Transforming & Copying the Glyph Image

If the glyph image is scalable (i.e., if glyph->format is not equal to FT_GLYPH_FORMAT_BITMAP), it is possible to transform the image anytime by a call to FT_Glyph_Transform.

You can also copy a single glyph image with FT_Glyph_Copy.

Note that the 2×2 transformation matrix is always applied to the 16.16 advance vector in the glyph; you thus don't need to recompute it.

c. Measuring the Glyph Image

You can also retrieve the control (bounding) box of any glyph image (scalable or not) through the FT_Glyph_Get_CBox function.

Coordinates are relative to the glyph origin (0,0), using the y upwards convention. This function takes a special argument, the bbox mode, to indicate how box coordinates are expressed.

If the glyph has been loaded with FT_LOAD_NO_SCALE, bbox_mode must be set to FT_GLYPH_BBOX_UNSCALED to get unscaled font units in 26.6 pixel format. The value FT_GLYPH_BBOX_SUBPIXELS is another name for this constant.

Note that the box's maximum coordinates are exclusive, which means that you can always compute the width and height of the glyph image (regardless of using integer or 26.6 coordinates) with a simple subtraction.

Note also that for 26.6 coordinates, if FT_GLYPH_BBOX_GRIDFIT is used as the bbox mode, the coordinates are also grid-fitted, which corresponds to the following four lines of pseudo-code.

To get the bbox in integer pixel coordinates, set bbox_mode to FT_GLYPH_BBOX_TRUNCATE.

Finally, to get the bounding box in grid-fitted pixel coordinates, set bbox_mode to FT_GLYPH_BBOX_PIXELS.

[Computing exact bounding boxes can be done with function FT_Outline_Get_BBox, at the cost of slower execution. You probably don't need it with the possible exception of rotated glyphs.]

d. Converting the Glyph Image to a Bitmap

You may need to convert the glyph object to a bitmap once you have conveniently cached or transformed it. This can be done easily with the FT_Glyph_To_Bitmap function, which handles any glyph object.

Some notes.

- The first parameter is the address of the source glyph's handle. When the function is called, it reads it to access the source glyph object. After the call, the handle points to a new glyph object that contains the rendered bitmap.

- The second parameter is a standard render mode to specify what kind of bitmap we want. For example, it can be

FT_RENDER_MODE_DEFAULTfor an 8-bit anti-aliased pixmap, orFT_RENDER_MODE_MONOfor a 1-bit monochrome bitmap. - The third parameter is a pointer to a two-dimensional vector to translate the source glyph image before the conversion. After the call, the source image is translated back to its original position (and is thus left unchanged). If you do not need to translate the source glyph before rendering, set this pointer to NULL.

- The last parameter is a boolean that indicates whether the source glyph object should be destroyed by the function. If false, the original glyph object is never destroyed, even if its handle is lost (it is up to client applications to keep it).

The new glyph object always contains a bitmap (if no error is returned), and you must typecast its handle to the FT_BitmapGlyph type in order to access its content. This type is a sort of ‘subclass' of FT_Glyph that contains additional fields (see FT_BitmapGlyphRec).

Glyph Designer 2 1 – Bitmap Font Generator Minecraft 1.7.10

- left

- Just like the

bitmap_leftfield of a glyph slot, this is the horizontal distance from the glyph origin (0,0) to the leftmost pixel of the glyph bitmap. It is expressed in integer pixels. - top

- Just like the

bitmap_topfield of a glyph slot, this is the vertical distance from the glyph origin (0,0) to the topmost pixel of the glyph bitmap (more precise, to the pixel just above the bitmap). This distance is expressed in integer pixels, and is positive for upwards y. - bitmap

- This is a bitmap descriptor for the glyph object, just like the

bitmapfield in a glyph slot.

3. Global Glyph Metrics

Unlike glyph metrics, global metrics are used to describe distances and features of a whole font face. They can be expressed either in 26.6 pixel format or in (unscaled) font units for scalable formats.

a. Design global metrics

For scalable formats, all global metrics are expressed in font units in order to be later scaled to the device space, according to the rules described in the last section of this tutorial part. You can access them directly as fields of an FT_Face handle.

However, you need to check that the font face's format is scalable before using them. One can do it with macro FT_IS_SCALABLE, which returns true when appropriate.

Here a table of the global design metrics for scalable faces.

- units_per_EM

- This is the size of the EM square for the font face. It is used by scalable formats to scale design coordinates to device pixels, as described in the last section of this tutorial part. Its value usually is 2048 (for TrueType) or 1000 (for Type 1 or CFF), but other values are possible, too. It is set to 1 for fixed-size formats like FNT, FON, PCF, or BDF.

- bbox

- The global bounding box is defined as the smallest rectangle that can enclose all the glyphs in a font face.

- ascender

- The ascender is the vertical distance from the horizontal baseline to the highest ‘character' coordinate in a font face. Unfortunately, font formats don't define the ascender in a uniform way. For some formats, it represents the ascent of all capital latin characters (without accents), for others it is the ascent of the highest accented character, and finally, other formats define it as being equal to

bbox.yMax. - descender

- The descender is the vertical distance from the horizontal baseline to the lowest ‘character' coordinate in a font face. Unfortunately, font formats don't define the descender in a uniform way. For some formats, it represents the descent of all capital latin characters (without accents), for others it is the ascent of the lowest accented character, and finally, other formats define it as being equal to

bbox.yMin. This field is negative for values below the baseline. - height

- This field represents a default line spacing (i.e., the baseline-to-baseline distance) when writing text with this font. Note that it usually is larger than the sum of the ascender and descender taken as absolute values. There is also no guarantee that no glyphs extend above or below subsequent baselines when using this distance – think of it as a value the designer of the font finds appropriate.

- max_advance_width

- This field gives the maximum horizontal cursor advance for all glyphs in the font. It can be used to quickly compute the maximum advance width of a string of text. It doesn't correspond to the maximum glyph image width!

- max_advance_height

- Same as

max_advance_widthbut for vertical text layout. - underline_position

- When displaying or rendering underlined text, this value corresponds to the vertical position, relative to the baseline, of the underline bar's center. It is negative if it is below the baseline.

- underline_thickness

- When displaying or rendering underlined text, this value corresponds to the vertical thickness of the underline.

Notice that the values of the ascender and the descender are not reliable (due to various discrepancies in font formats), unfortunately.

b. Scaled Global Metrics

Each size object also contains a scaled version of some of the global metrics described above, to be directly accessed through the face->size->metrics structure (of type FT_Size_Metrics). No grid-fitting is performed for those values. They are also completely independent of any hinting process. In other words, don't rely on them to get exact metrics at the pixel level. They are expressed in 26.6 pixel format but rounded for historical reasons.

The scaled version of the original design text height (the vertical distance from one baseline to the next). This is probably the only field you should really use in this structure. It is rounded to an integer value.

Be careful not to confuse it with the ‘height' field in the FT_Glyph_Metrics structure.

Note that the face->size->metrics structure contains other fields that are used to scale design coordinates to device space. They are described in the last section.

c. Kerning

Kerning is the process of adjusting the position of two subsequent glyph images in a string of text in order to improve the general appearance of text. For example, if a glyph for an uppercase ‘A' is followed by a glyph for an uppercase ‘V', the space between the two glyphs can be slightly reduced to avoid extra ‘diagonal whitespace'.

Note that in theory kerning can happen both in the horizontal and vertical direction between two glyphs; however, it only happens in a single direction in nearly all cases.

Not all font formats contain kerning information, and not all kerning formats are supported by FreeType; in particular, for TrueType fonts, the API can only access kerning via the ‘kern' table. OpenType kerning via the ‘GPOS' table is not supported! You need a higher-level library like HarfBuzz, Pango, or ICU, since GPOS kerning requires contextual string handling.

Sometimes, the font file is associated with an additional file that contains various glyph metrics, including kerning, but no glyph images. A good example is the Type 1 format where glyph images are stored in files with extension .pfa or .pfb, while kerning metrics can be found in files with extension .afm or .pfm.

FreeType 2 allows you to deal with this, by providing the FT_Attach_File and FT_Attach_Stream APIs. Both functions are used to load additional metrics into a face object by reading them from an additional format-specific file. Here an example, opening a Type 1 font.

Note that FT_Attach_Stream is similar to FT_Attach_File except that it doesn't take a C string to name the extra file but an FT_Stream handle. Also, reading a metrics file is in no way mandatory.

Finally, the file attachment APIs are very generic and can be used to load any kind of extra information for a given face. The nature of the additional content is entirely font format specific.

FreeType 2 allows you to retrieve the kerning information between two glyphs through the FT_Get_Kerning function.

This function takes a handle to a face object, the indices of the left and right glyph for which the kerning value is desired, an integer, called the kerning mode, and a pointer to a destination vector that receives the corresponding distances.

The kerning mode is very similar to the bbox mode described in a previous section. It is a enumeration that indicates how the kerning distances are expressed in the target vector.

The default value is FT_KERNING_DEFAULT, which has value 0. It corresponds to kerning distances expressed in 26.6 grid-fitted pixels (which means that the values are multiples of 64). For scalable formats, this means that the design kerning distance is scaled, then rounded.

The value FT_KERNING_UNFITTED corresponds to kerning distances expressed in 26.6 unfitted pixels (i.e., that do not correspond to integer coordinates). It is the design kerning distance that is scaled without rounding.

Finally, the value FT_KERNING_UNSCALED indicates to return the design kerning distance, expressed in font units. You can later scale it to the device space using the computations explained in the last section of this part.

Note that the ‘left' and ‘right' positions correspond to the visual order of the glyphs in the string of text. This is important for bidirectional or right-to-left text.

4. Simple Text Rendering: Kerning and Centering

In order to show off what we have just learned, we now demonstrate how to modify the example code that was provided in part I to render a string of text, and enhance it to support kerning and delayed rendering.

a. Kerning Support

Adding support for kerning to our code is trivial, as long as we consider that we are still dealing with a left-to-right script like Latin. We simply need to retrieve the kerning distance between two glyphs in order to alter the pen position appropriately.

We are done. Some notes.

- As kerning is determined by glyph indices, we need to explicitly convert our character codes into glyph indices, then later call

FT_Load_Glyphinstead ofFT_Load_Char. - We use a boolean named

use_kerning, which is set to the result of the macroFT_HAS_KERNING. It is certainly faster not to callFT_Get_Kerningwhen we know that the font face does not contain kerning information. - We move the position of the pen before a new glyph is drawn.

- We initialize the variable

previouswith the value 0, which always corresponds to the ‘missing glyph' (also called.notdefin the PostScript world). There is never any kerning distance associated with this glyph. - We do not check the error code returned by

FT_Get_Kerning. This is because the function always sets the content ofdeltato (0,0) if an error occurs.

b. Centering

Our code begins to become interesting but it is still a bit too simple for normal use. For example, the position of the pen is determined before we do the rendering; normally, you would rather determine the layout of the text and measure it before computing its final position (centering, etc.), or perform things like word-wrapping.

Let us now decompose our text rendering function into two distinct but successive parts: The first one positions individual glyph images on the baseline, while the second one renders the glyphs. As we will see, this has many advantages.

We thus start by storing individual glyph images, as well as their position on the baseline.

This is a very slight variation of our previous code; we extract each glyph image from the slot, then store it, along with the corresponding position, in our tables.

Note also that pen_x contains the total advance for the string of text. We can now compute the bounding box of the text string with a simple function.

The resulting bounding box dimensions are expressed in integer pixels and can then be used to compute the final pen position before rendering the string.

In general, the above function does not compute an exact bounding box of a string! As soon as hinting is involved, glyph dimensions must be derived from the resulting outlines. For anti-aliased pixmaps, FT_Outline_Get_BBox then yields proper results. In case you need 1-bit monochrome bitmaps, it is even necessary to actually render the glyphs because the rules for the conversion from outline to bitmap can also be controlled by hinting instructions (cf. dropout control).

Some remarks.

- The pen position is expressed in the Cartesian space (i.e., y upwards).

- We call

FT_Glyph_To_Bitmapwith thedestroyparameter set to 0 (false), in order to avoid destroying the original glyph image. The new glyph bitmap is accessed throughimageafter the call and is typecast toFT_BitmapGlyph. - We use translation when calling

FT_Glyph_To_Bitmap. This ensures that theleftandtopfields of the bitmap glyph object are already set to the correct pixel coordinates in the Cartesian space. - Of course, we still need to convert pixel coordinates from Cartesian to device space before rendering, hence the

my_target_height - bitmap->topin the call tomy_draw_bitmap.

The same loop can be used to render the string anywhere on our display surface, without the need to reload our glyph images each time.

5. Advanced Text Rendering: Transformation and Centering and Kerning

We are now going to modify our code in order to be able to easily transform the rendered string, for example, to rotate it. First, some minor improvements.

a. Packing and Translating Glyphs

We start by packing the information related to a single glyph image into a single structure instead of parallel arrays.

We also translate each glyph image directly after it is loaded to its position on the baseline at load time. As we will see, this has several advantages. Here is our new glyph sequence loader.

Glyph Designer 2 1 – Bitmap Font Generator Minecraft Download

Nitro pdf for mac free version. Note that translating glyphs now has several advantages. The first one is that we don't need to translate the glyph bbox when we compute the string's bounding box.

With the above modifications, the compute_string_bbox function can now compute the bounding box of a transformed glyph string, which allows further code simplications.

b. Rendering a Transformed Glyph Sequence

However, directly transforming the glyphs in our sequence is not a good idea if we want to reuse them in order to draw the text string with various angles or transformations. It is better to perform the affine transformation just before the glyph is rendered.

There are a few changes compared to the original version of this code.

- We keep the original glyph images untouched; instead, we transform a copy.

- We perform clipping computations in order to avoid rendering and drawing glyphs that are not within our target surface.

- We always destroy the copy when calling

FT_Glyph_To_Bitmapin order to get rid of the transformed scalable image. Note that the image is not destroyed if the function returns an error code (which is whyFT_Done_Glyphis only called within the compound statement). - The translation of the glyph sequence to the start pen position is integrated into the call to

FT_Glyph_Transforminstead ofFT_Glyph_To_Bitmap.

It is possible to call this function several times to render the string with different angles, or even change the way start is computed in order to move it to different place.

This code is the basis of the FreeType 2 demonstration program named ftstring.c. It could be easily extended to perform advanced text layout or word-wrapping in the first part, without changing the second one.

Note, however, that a normal implementation would use a glyph cache in order to reduce memory needs. For example, let us assume that our text string is ‘FreeType'. We would store three identical glyph images in our table for the letter ‘e', which isn't optimal (especially when you consider longer lines of text, or even whole pages).

A FreeType demo program that shows how glyph caching can be implemented is ftview.c. In general, ‘ftview' is the main program used by the FreeType developer team to check the validity of loading, parsing, and rendering fonts.

Another very useful demo program is ftdiff.c, demonstrating the use and the optical results of the various rendering and hinting modes provided by FreeType. In particular, it also demonstrates how to do sub-pixel positioning (for unhinted glyphs and ‘light' hinting mode) – all code in this tutorial assumes integer coordinates.

6. Accessing Metrics in Design Font Units, and Scaling Them

Scalable font formats usually store a single vectorial image, called an outline, for each glyph in a face. Each outline is defined in an abstract grid called the design space, with coordinates expressed in font units. When a glyph image is loaded, the font driver usually scales the outline to device space according to the current character pixel size found in an FT_Size object. The driver may also modify the scaled outline in order to significantly improve its appearance on a pixel-based surface (a process known as hinting or grid-fitting).

This section describes how design coordinates are scaled to the device space, and how to read glyph outlines and metrics in font units. This is important for a number of things.

- ‘True' WYSIWYG text layout.

- Accessing font content for conversion or analysis purposes.

a. Scaling Distances to Device Space

Design coordinates are scaled to the device space using a simple scaling transformation whose coefficients are computed with the help of the character pixel size.

Here, the value EM_size is font-specific and corresponds to the size of an abstract square of the design space (called the EM), which is used by font designers to create glyph images. It is thus expressed in font units. It is also accessible directly for scalable font formats as face->units_per_EM. You should check that a font face contains scalable glyph images by using the FT_IS_SCALABLE macro, which returns true if appropriate.

When you call the function FT_Set_Pixel_Sizes, you are specifying integer values of pixel_size_x and pixel_size_y FreeType shall use. The library will immediately compute the values of x_scale and y_scale.

When you call the function FT_Set_Char_Size, you are specifying the character size in physical points, which is used, along with the device's resolutions, to compute the character pixel size and the corresponding scaling factors. Here, the scaling factors can correspond to fractional ppem values.

Note that after calling any of these two functions, you can access the values of the character pixel size and scaling factors as fields of the face->size->metrics structure.

- x_ppem

- The field name stands for ‘x pixels per EM'; this is the horizontal size rounded to integer pixels of the EM square, which also is the horizontal character pixel size, called

pixel_size_xin the above example. - y_ppem

- The field name stands for ‘y pixels per EM'; this is the vertical size rounded to integer pixels of the EM square, which also is the vertical character pixel size, called

pixel_size_yin the above example. - x_scale

- This is a 16.16 fixed-point scale to directly scale horizontal distances from design space to 1/64th of device pixels.

- y_scale

- This is a 16.16 fixed-point scale to directly scale vertical distances from design space to 1/64th of device pixels.

You can scale a distance expressed in font units to 26.6 pixel format directly with the help of the FT_MulFix Templates bundle for iwork 5 0. function.

Alternatively, you can also scale the value directly by using doubles.

b. Accessing Design Metrics (Glyph & Global)

You can access glyph metrics in font units simply by specifying the FT_LOAD_NO_SCALE bit flag in FT_Load_Glyph or FT_Load_Char. The metrics returned in face->glyph->metrics will all be in font units.

You can access unscaled kerning data using the FT_KERNING_MODE_UNSCALED mode.

Finally, a few global metrics are available directly in font units as fields of the FT_Face handle, as described in section 3 of this part.

Conclusion

This is the end of the second part of the FreeType tutorial. You are now able to access glyph metrics, manage glyph images, and render text much more intelligently (kerning, measuring, transforming & caching); this is sufficient knowledge to build a pretty decent text service on top of FreeType.

The demo programs in the ‘ft2demos' bundle (especially ‘ftview') are a kind of reference implementation, and are a good resource to turn to for answers. They also show how to use additional features, such as the glyph stroker and cache.

II. Glyph Outlines

This section describes the way scalable representations of glyph images, called outlines, are used by FreeType as well as client applications.

1. Pixels, points, and device resolutions

Though it is a very common assumption when dealing with computer graphics programs, the physical dimensions of a given pixel (be it for screens or printers) are not squared. Often, the output device exhibits varying resolutions in both horizontal and vertical directions, and this must be taken care of when rendering text.

It is thus common to define a device's characteristics through two numbers expressed in dpi (dots per inch). For example, a printer with a resolution of 300×600 dpi has 300 pixels per inch in the horizontal direction, and 600 in the vertical one. The resolution of a typical computer monitor varies with its size (10″ and 25″ monitors don't have the same pixel sizes at 1024×768), and of course the graphics mode resolution.

As a consequence, the size of text is usually given in points, rather than device-specific pixels. Points are a physical unit, where 1 point equals 1/72th of an inch in digital typography. As an example, most books using the Latin script are printed with a body text size somewhere between 10 and 14 points.

It is thus possible to compute the size of text in pixels from the size in points with the following formula:

pixel_size = point_size * resolution / 72The resolution is expressed in dpi. Since horizontal and vertical resolutions may differ, a single point size usually defines a different text width and height in pixels.

Unlike what is often thought, the ‘size of text in pixels' is not directly related to the real dimensions of characters when they are displayed or printed. The relationship between these two concepts is a bit more complex and depends on some design choices made by the font designer. This is described in more detail in the next sub-section (see the explanations on the EM square).

2. Vectorial representation

The source format of outlines is a collection of closed paths called contours. Each contour delimits an outer or inner region of the glyph, and can be made of either line segments or Bézier arcs.

The arcs are defined through control points, and can be either second-order (these are conic Béziers) or third-order (cubic Béziers) polynomials, depending on the font format. Note that conic Béziers are usually called quadratic Béziers in the literature. Hence, FreeType associates each point of the outline with flags to indicate its type (normal or control point). As a consequence, scaling the points will scale the whole outline.

Each glyph's original outline points are located on a grid of indivisible units. The points are usually stored in a font file as 16-bit integer grid coordinates, with the grid's origin being at (0,0); they thus range from -32768 to 32767. (Even though point coordinates can be floats in other formats such as Type 1, we will restrict our analysis to integer values for simplicity).

The grid is always oriented like the traditional mathematical two-dimensional plane, i.e., the X axis goes from the left to the right, and the Y axis from bottom to top.

In creating the glyph outlines, a type designer uses an imaginary square called the EM square. Typically, the EM square can be thought of as a tablet on which the characters are drawn. The square's size, i.e., the number of grid units on its sides, is very important for two reasons:

It is the reference size used to scale the outlines to a given text dimension. For example, a size of 12pt at 300×300 dpi corresponds to 12*300/72 = 50 pixels. This is the size the EM square would appear on the output device if it was rendered directly. In other words, scaling from grid units to pixels uses the formula:

pixel_size = point_size * resolution / 72pixel_coord = grid_coord * pixel_size / EM_sizeAnother acronym used for the pixel size is ppem (pixel per EM); this value can be fractional also. Note that fractional ppem values are not supported everywhere.

The greater the EM size is, the larger resolution the designer can use when digitizing outlines. For example, in the extreme example of an EM size of 4 units, there are only 25 point positions available within the EM square which is clearly not enough. Typical TrueType fonts use an EM size of 2048 units; Type 1 or CFF PostScript fonts traditionally use an EM size of 1000 grid units (but point coordinates can be expressed as floating values).

Note that glyphs can freely extend beyond the EM square if the font designer wants so. The EM square is thus just a convention in traditional typography.

Grid units are very often called font units or EM units.

As said before, pixel_size computed in the above formula does not directly relate to the size of characters on the screen. It simply is the size of the EM square if it was to be displayed. Each font designer is free to place its glyphs as it pleases him within the square. This explains why the letters of the following text have not the same height, even though they are displayed at the same point size with distinct fonts:

As one can see, the glyphs of the Courier family are smaller than those of Times New Roman, which themselves are slightly smaller than those of Arial, even though everything is displayed or printed at a size of 16 points. Xtrafinder serial crack. This only reflects design choices.

3. Hinting and Bitmap rendering

The outline as stored in a font file is called the ‘master' outline, as its point coordinates are expressed in font units. Before it can be converted into a bitmap, it must be scaled to a given size and resolution. This is done with a very simple transformation, but especially at small sizes undesirable artifacts can appear, in particular stems of different width or height in letters like ‘E' or ‘H' can occur.

As a consequence, proper glyph rendering needs the scaled points to be aligned along the target device pixel grid, through an operation called grid-fitting (often called hinting). One of its main purposes is to ensure that important widths and heights are respected throughout the whole font (for example, it is very often desirable that the ‘I' and the ‘T' glyphs have their central vertical line of the same pixel width), as well as to manage features like stems and overshoots, which can cause problems at small pixel sizes.

There are several ways to perform grid-fitting properly; most scalable formats associate some control data or programs with each glyph outline. Here is an overview:

explicit grid-fitting

The TrueType format defines a stack-based virtual machine, for which programs (also called bytecode) can be written with the help of more than 200 operators, most of them related to geometrical operations. Each glyph is thus made of both an outline and a control program to perform the actual grid-fitting in the way defined by the font designer.

implicit grid-fitting (also called hinting)

The Type 1, CFF, and CFF2 formats take a much simpler approach: Each glyph is made of an outline as well as several pieces called hints which are used to describe some important features of the glyph, like the presence of stems, some width regularities, and the like. There aren't a lot of hint types, and it is up to the final renderer to interpret the hints in order to produce a fitted outline.

automatic grid-fitting

Some formats include no control information with each glyph outline, apart from font metrics like the advance width and height. It is then up to the renderer to ‘guess' the more interesting features of the outline in order to perform some decent grid-fitting.

The following table summarizes the pros and cons of each scheme.

| grid-fitting scheme | advantages | disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

explicit | Quality. Excellent results at small sizes are possible. This is very important for screen display. Consistency. This document has certain edit capabilities mac. All renderers produce the same glyph bitmaps (at least in theory). | Speed. Interpreting bytecode can be slow if the glyph programs are complex. Size. Glyph programs can be long. Technical difficulty. It is extremely difficult to write good hinting programs. Very few tools available. |

implicit | Size. Hints are usually much smaller than explicit glyph programs. Speed. Grid-fitting is usually a fast process. | Quality. Often questionable at small sizes. Better with anti-aliasing though. Inconsistency. Results can vary between different renderers, or even distinct versions of the same engine. |

automatic | Size. No need for control information, resulting in smaller font files. Speed. Depends on the grid-fitting algorithm. Usually faster than explicit grid-fitting. | Quality. Often questionable at small sizes. Better with anti-aliasing though. Speed. Depends on the grid-fitting algorithm. Inconsistency. Results can vary between different renderers, or even distinct versions of the same engine. |